Why the Fed fears cutting interest rates too soon

The 1970s-style potential inflation resurgence gives Jerome Powell and other Fed members nightmares

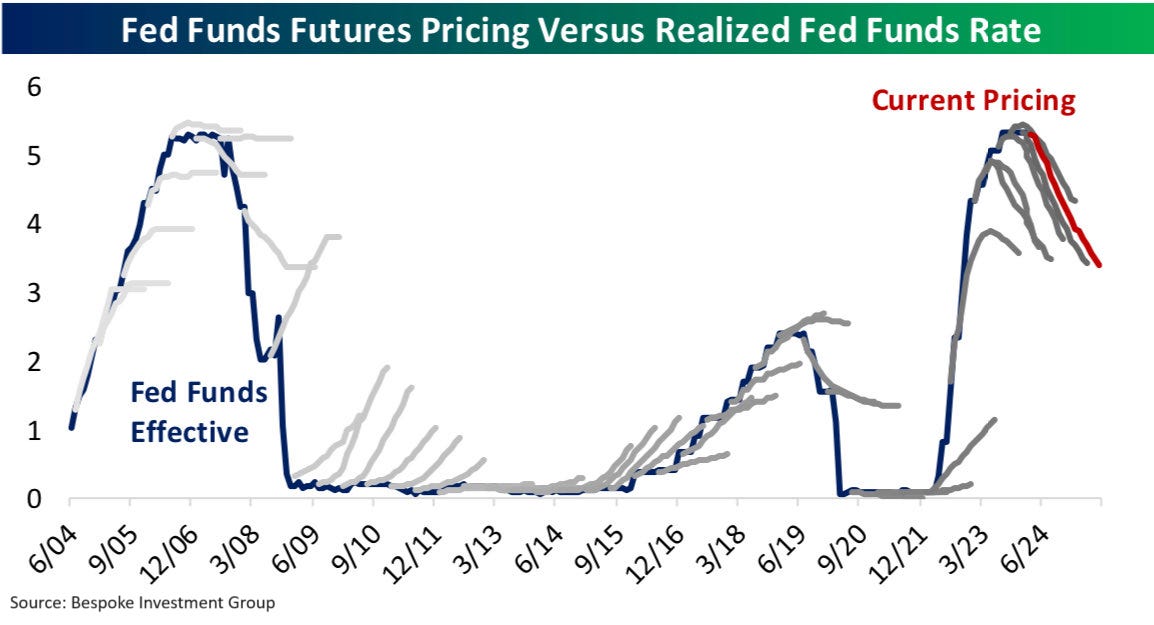

On Thursday, February 1, 2024, 60 Minutes correspondent Scott Pelley interviewed Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve Chairman at the Central Bank headquarters in Washington, D.C. The interview has been released on Sunday, February 4, 2024. The interview itself has not brought up anything new. Powell more or less reiterated what he said during his last press FOMC press conference on January 31, 2024, that the March interest rate cut is off the table as well as the Fed needs more confidence and evidence about the inflation moving sustainably down to 2%. This is another example of the Fed sticking to its playbook no matter what the market thinks and when the S&P 500 goes. And rightly so. It does not matter that before the Fed meeting the market had been pricing almost a 50% chance of a cut in March. As you can see on the below chart, the market is wrong more than 90% of the time in accurately predicting the pace and the timing of interest rate moves and unless you are a short-term trader or a rates trader the market pricing should not bother you much.

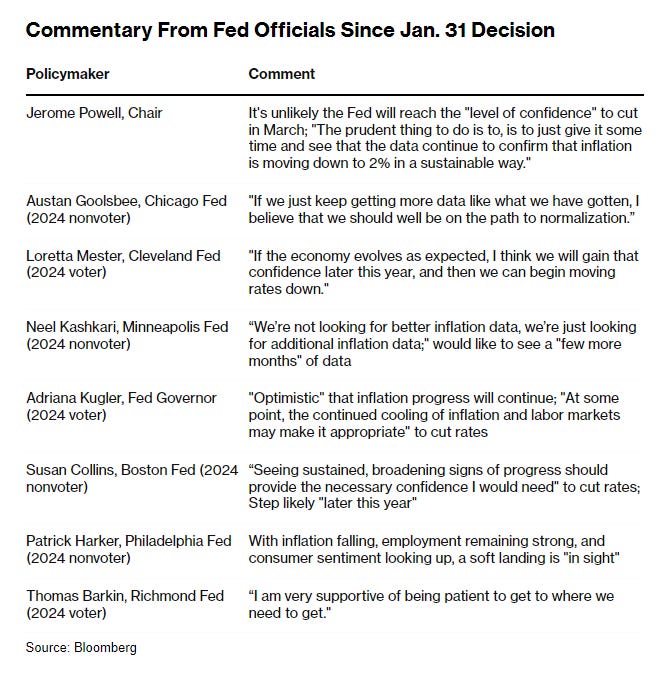

Indeed, in the past few weeks, all the talk of the Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members was about getting more confidence and more good data to start implementing their forecast of “just” three rate cuts this year versus the market expectations of almost six. Below is the summary of the speeches since the January 31st meeting.

This is in fact nothing else than expressing the fear of inflation resurgence and a complete loss of an already damaged reputation (calling inflation ‘transitory’ in 2021 and 2022 was one of the worst calls in the Fed history). In other words, the fear of repeating the 1970s scenario.

WHAT EXACTLY HAPPENED IN THE 1970s?

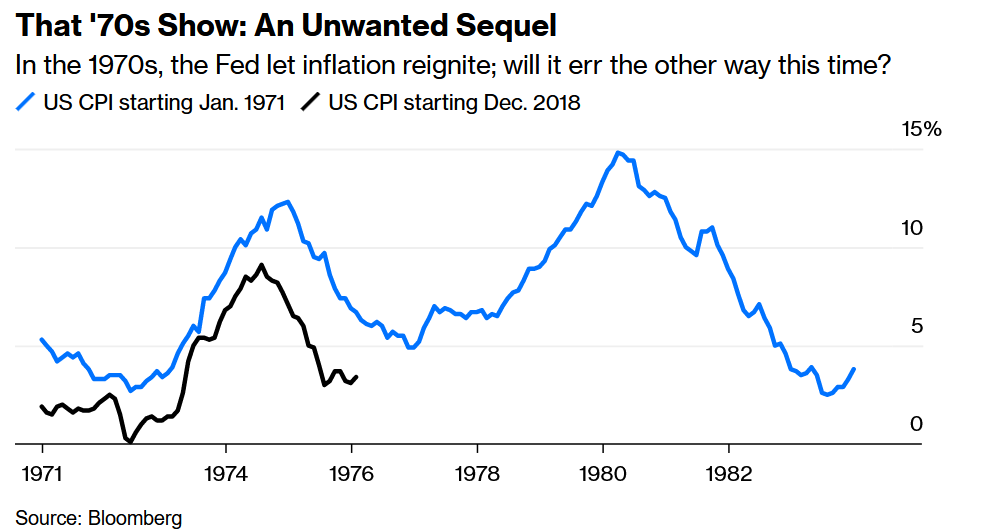

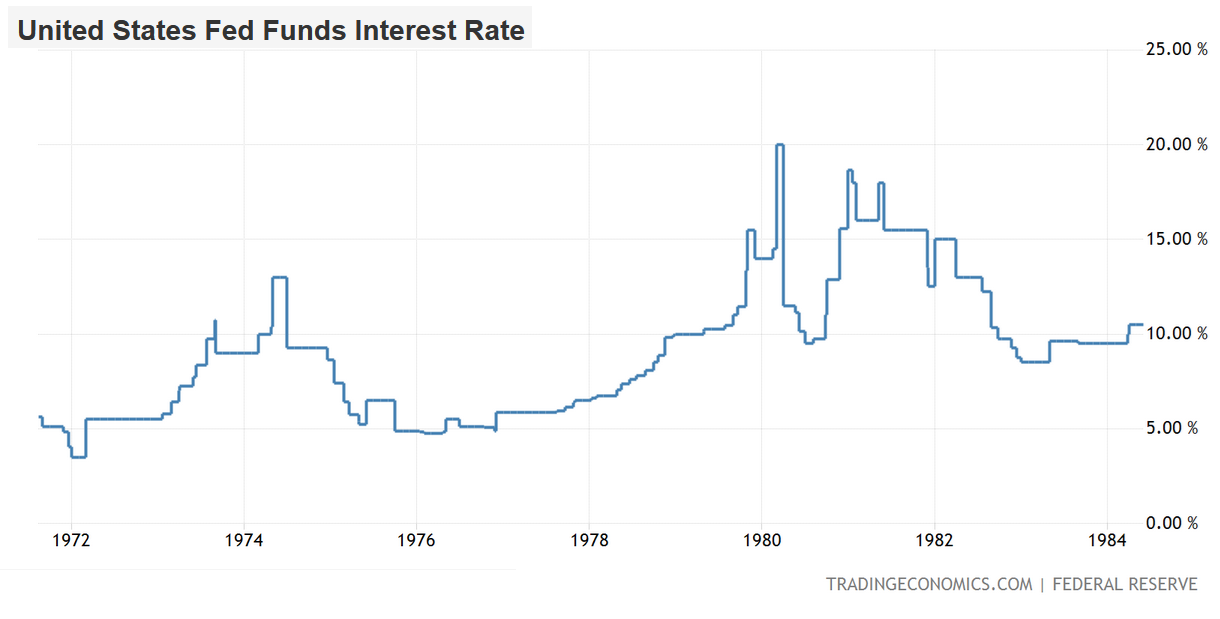

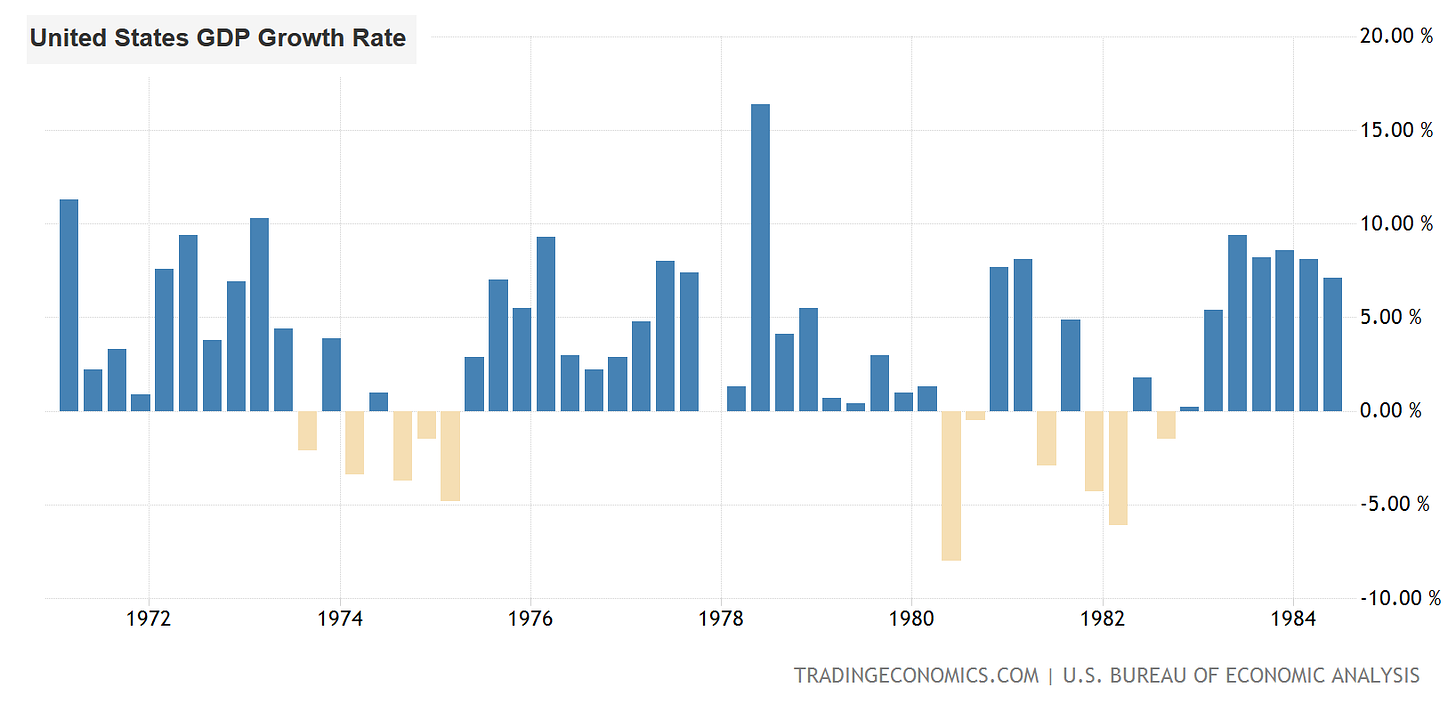

In the 1970s the Federal Reserve under the leadership of Arthur Burns (in office January 31, 1970 – March 31, 1978) made the largest policy mistake since the Great Depression. In the early years of the decade inflation rate bottomed and started to rapidly rise similarly as in the 2021-2022 period. Months before December 1974 when inflation peaked Burns started to cut interest rates. Subsequently, inflation had been falling as the US economy had been going through a recession. However, it had never consistently fallen below 5% during that time. After 1975, the US GDP growth turned positive and inflation started rising again but from a much higher base than previously (~3%) reaching almost 15% in 1980 on a year-over-year basis. It was clear that the interest rate reductions had been conducted too soon. In 1979, Paul Volcker became the Fed chair and in order to fight this started to raise rates to 20%. Following this he cut them below 10% fighting an abrupt recession and after that raising them once again to roughly 18%. By the mid-1983, the inflation rate had fallen to 2.5%. Due to this successful fight, Paul Volcker is now regarded as one of the most prominent Fed chairmen in history as he understood the economic forces that caused elevated inflation in the United States. However, we have to remember that the economy also felt short-term pain during that time.

This series of events brought a really important lesson for the successors: don’t ever cut interest rates too soon. The entire story is well explained by the three charts attached below. The first one also shows the current inflation path (black line) which provides a warning sign of a potential sequel of the 1970s.

DON’T BE LIKE ARTHUR BURNS BE LIKE PAUL VOLCKER

It is clear that the Fed does not want to repeat this severe in-consequence mistake from the 1970s and Jerome Powell does not want to be the next Arthur Burns. This is why the Fed prefers to wait and see more data and observe whether inflation will pick up again in the first half of the year. Another important argument that they might have been keeping in mind is that the later the first interest rate cut occurs the more rate cuts in reserve the central bank will have in case of an economic downturn. This might help the Fed from not going back to zero interest rates (zero-bound) which are regarded as abnormal.

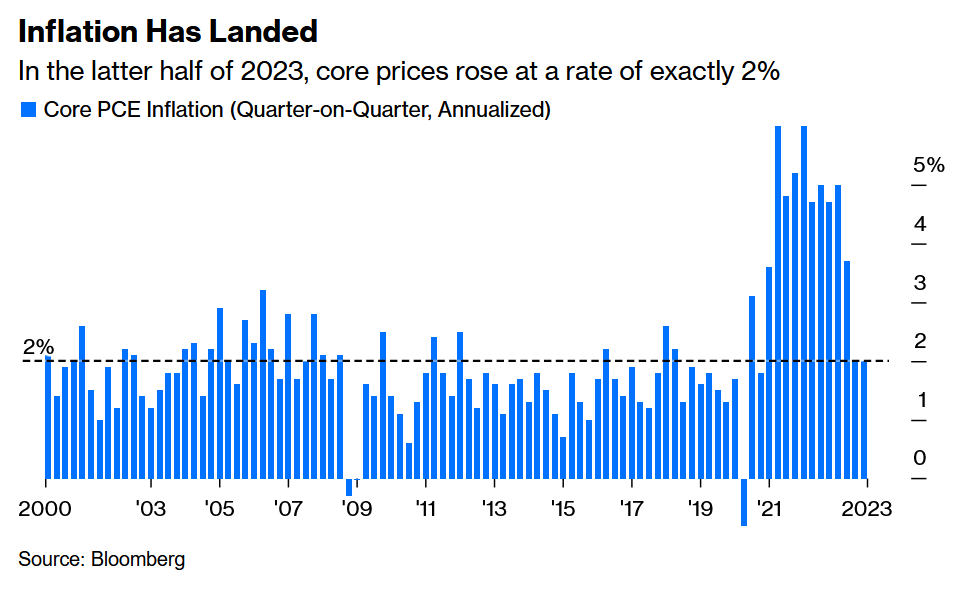

Looking at the current inflation rates, core PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure excluding food and energy, preferred Fed gauge) measured from quarter to quarter has already reached the 2% target in 3Q and 4Q of 2023.

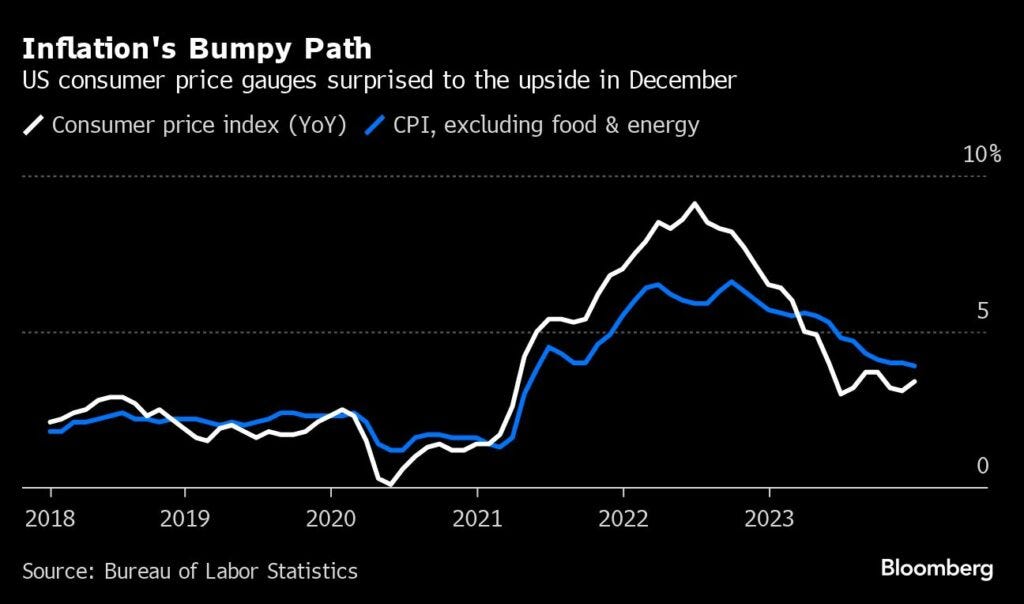

However, the CPI (Consumer Price Index inflation), and core CPI have plateaued in the last couple of months reaching 3.4% and 3.9% in December, respectively. When you look at the chart above, the white line does not look like it is coming toward 2%.

Therefore, it might be indeed prudent to wait and see what will happen in the next few months. In the 60 Minutes interview, Jerome Powell mentioned that it would be appropriate to wait until the middle of the year. Will it be May, June, or July? Further inflation and labor market data such as net job gains and wage increases should help to decide.

SUMMARY

18 months ago, the CPI inflation rate in the US reached its peak of 9.1%, subsequently fell to roughly 3.5% showing a similar direction as in the 1970s, and has been stubbornly staying around there. This phenomenon certainly gives Fed Chairman Jerome Powell nightmares and reminds him of Arthur Burns. This is even though the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge is core PCE which has already reached the institution's target of 2%. It is obvious that no one wants to be regarded as one of the worst leaders in the history of the largest and most important central bank in the world. For that reason, given the current CPI inflation rate and other economic data, the Fed will be waiting for the first interest rate cut as long as possible to avoid making the largest monetary policy mistake in this century and completely losing its already significantly ruined reputation.

If you find it informative and helpful you may consider buying me a coffee and follow me on Twitter:

The US suppressed oil and gold prices worldwide after WW2, and after overspending in Vietnam this suppression stopped working. LBJ stopped allowing other countries to trade dollars for gold while he was still President, Nixon followed suit, and finally announced the policy in '71, and this was recorded as "Nixon slammed shut the gold window".

This "end of suppression" caused the major repricing of gold and oil in the 70s, and this the major cause of the 70s inflation. How Burns handled it, well, he didn't have many tools, and Volcker didn't either. Pinning all of the 70s price action on the Fed is... very wrong.